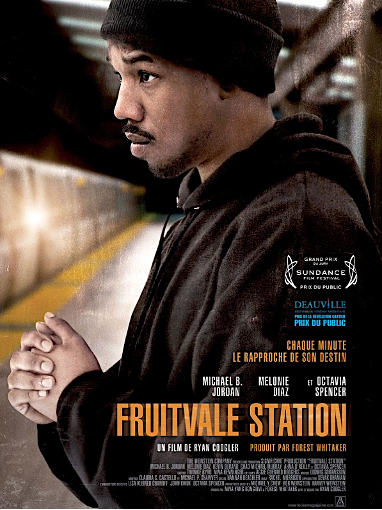

A Life Derailed at “Fruitvale Station”

Fruitvale Station

2013 Director: Ryan Coogler

Starring: Michael B. Jordan, Melonie Diaz, Octavia Spencer

I remember hearing the news that Oscar Grant was killed that day in 2008. We were in the kitchen. We were in disbelief. How many times had I stood on that same platform as him before this happened? Yet another Black man senselessly gunned down in his prime. Those of us who knew Fruitvale so well took it personally. Grant’s story became a film entitled “Fruitvale Station” in 2013. It received the Best Film Award that year at the Cannes Film Festival. The American Film Institute named it one of the top ten films of the year. The drama and its director were also honored at the Sundance Film Festival.

The movie begins with actual footage of the last moments of Grant’s life, captured on a bystander’s cellphone. Grant and three male friends sit on the station’s platform, as ordered by BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) police, who responded to a fistfight on a crowded train that fateful New Year’s Eve. Revelers were returning home in the early dawn hours from San Francisco. The police were aggressive and abusive towards the men, one of the cops shot Grant in the back after being handcuffed. Watching him restrained, face down on the pavement, now recalls the murder of George Floyd by police in 2020.

“Fruitvale” avoids a biographic slant; instead, it primarily tracks a few of the last mundane events of Grant’s life. Grant (Jordan) and his family are preparing for his mother’s (Spencer), birthday the next day. Someone needs to get the cake and a nice birthday card. Writer and director Ryan Coogler humanizes Grant for the viewer; he is no longer just some statistic, some name and face in the news. Indeed, Coogler helps us get to know the victims of this tragedy, of which there are several, particularly his daughter, Tatiana (Ariana Neal), who would have to grow up without a father.

Grant is no hero, but neither is he a villain. And he also doesn’t have to look for trouble; it finds him easily and constantly, as it happens to many inner-city young men. His girlfriend, Sophina (Diaz), is angry because of his recent infidelity. He lost his job at Farmer Joe’s grocery store for tardiness and is unsuccessful in recovering it. A flashback to 2007 describes a fight he had with an inmate at San Quentin. On the BART train that fateful night, an acquaintance greets Grant. The inmate, riding that same packed car, hears his name and seeks revenge for a previous quarrel they had. Yes; trouble is everywhere for everyone, but the film makes it clear that minorities and the poor frequently pay dearly for any indiscretion, infraction, and even for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. When Grant’s mother discovers he was shot at BART, she feels responsible. She asked him to take the train instead of driving to avoid any problems.

Two minor elements in this film bother me. One: nobody, but nobody calls The City “Frisco,” unless they are movie gangsters from the ‘40s or ‘50s. Any local would wince and wonder from what time warp you emerged if you said you were headed to “Frisco.” The other is the shaky camera technique used, particularly during action scenes. I’m glad filmmakers rarely use it anymore because it’s distracting. The human eye never sees events this way—the jerky effect simply reinforces the fact that one is watching a film and strains its credibility. Nevertheless, this film is haunting and thought-provoking. It shows the mean streets of Oakland’s Fruitvale neighborhood and its effects on its denizens. And, by the way, any fruit from Fruitvale was certainly long gone before Grant or I ever arrived there.